Navigation in multi module Android Compose UI project + Hilt

If you’ve written an Android application you must have had some form of navigation inside your project, whether that’s manually starting Activities or managing Fragment transactions on your own (hopefully you didn’t have to do this) or using navigation component, this is an article for you.

As you know Google released a terribly named UI toolking that’s just basically a compiler plugin on top of Kotlin to build Android UI, for more information about this read Jake’s blogpost.

Shortcomings of Navigation-compose

Google also released navigation component for Compose and it has it’s shortcomings, especially with multi modular applications.

Why?

You need to use the navigation controller to navigate to a destination, this produces

- NavHostController reference in Composable functions

- We need the instance produced by

rememberNavControllerin order to navigate somewhere. - This instance won’t allow us to easily test navigation as it does make us reliant on the instance provided either as a function parameter or a LocalProvider which both can be shooting yourself in the foot

- We need the instance produced by

- Easier testing

- As Mentioned in #1

- Modularization approach

- In order for you to navigate to a destination, using the navController will require you to have inclusion of the navigation dependency, which won’t make sense to use in a multi module project.

- The destination doesn’t have to know about the UI, it can be separated from the logic as well, since in compose we only navigate through routes built of

Strings. - Going back from current destination requires also the

navControllerinstance just to callnavigateUpwhich is painful when you might only need this, imagine navigating to a details screen and there you only have a back button, adding the whole navigation controller instance doesn’t make much sense. - Reusability, let’s say you want to go from A > B, B > C, C > D, D > B, the problem arises when going from D > B, in our approach D can include the navigation logic and know how to get to B, same as A, by just re-using the navigation routes we’ll make our lives easier.

There are probably more whys, I just haven’t got to them yet.

Building our navigation module

Every destination has two things in common.

- Route

- Arguments

For that matter we create our contract

1

2

3

4

5

6

fun interface NavigationDestination {

fun route(): String

val arguments: List<NamedNavArgument>

get() = emptyList()

}

You might ask yourself, why’s this a functional interface?

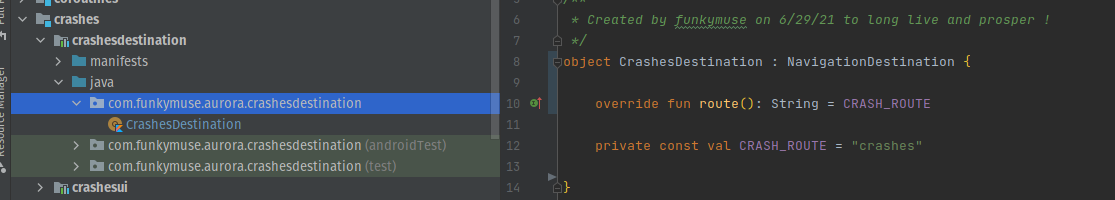

Sometimes you might never add arguments, for example your app provide crash reports on your own, your user can navigate from Settings > Crash reports, for that case we have a default for our arguments and the route has to be included every time.

The other building block we need is the events, every app has a navigate to and navigate from, of course this doesn’t stop you to add more events as they can be tailored to your use case, these are the most commonly used, for that purpose we have our Navigator

1

2

3

4

5

6

interface Navigator {

fun navigateUp(): Boolean

fun navigate(route: String, builder: NavOptionsBuilder.() -> Unit = { launchSingleTop = true }): Boolean

val destinations: Channel<NavigatorEvent>

}

The most confusing part here is the { launchSingleTop = true }, since we mostly need only one instance at a time when navigating to a composable screen, that’s the default for the NavOptionsBuilder since we are leveraging the following function from the navigation controller, you can tailor to your own one it doesn’t matter, consider this as it should be your guide towards your own use case.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

/**

* Navigate to a route in the current NavGraph. If an invalid route is given, an

* [IllegalArgumentException] will be thrown.

*

* @param route route for the destination

* @param builder DSL for constructing a new [NavOptions]

*

* @throws IllegalArgumentException if the given route is invalid

*/

public fun navigate(route: String, builder: NavOptionsBuilder.() -> Unit) {

navigate(route, navOptions(builder))

}

We need events for the navigator, sealed classes are our best friends here

1

2

3

4

sealed class NavigatorEvent {

object NavigateUp : NavigatorEvent()

class Directions(val destination: String, val builder: NavOptionsBuilder.() -> Unit) : NavigatorEvent()

}

and we also need something to handles our events, with the help of Hilt as we tend to reuse this we have to implement our navigator

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

@Singleton

internal class NavigatorImpl @Inject constructor() : Navigator {

private val navigationEvents = Channel<NavigatorEvent>()

override val destinations = navigationEvents.receiveAsFlow()

override fun navigateUp(): Boolean = navigationEvents.trySend(NavigatorEvent.NavigateUp).isSuccess

override fun navigate(route: String, builder: NavOptionsBuilder.() -> Unit): Boolean = navigationEvents.trySend(NavigatorEvent.Directions(route, builder)).isSuccess

}

in our NavigatorImpl we mimick the navController navigate and navigateUp functions but built on coroutines to try and handle successful navigations or not with the boolean callback but relying on the channel’s implementation for that, trySend doesn’t block, you can have the navigateUp as a suspend function in order to have more granular control of the Job returned but I didn’t see any need for that.

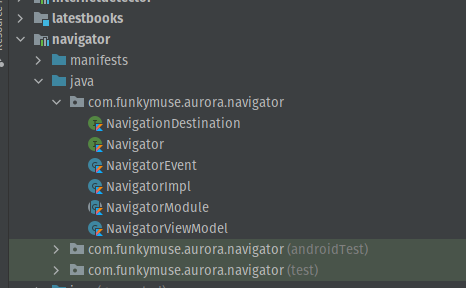

Sweet Hilt helps us with exposing the Navigator only while keeping the implementation internal to the module as you might have noticed NavigatorImpl has internal modifier.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

@Module

@InstallIn(SingletonComponent::class)

internal abstract class NavigatorModule {

@Binds

abstract fun navigator(navigator: NavigatorImpl): Navigator

}

That’s not all, since we already build our module sometimes we might only need navigation logic, but we can’t get that with Hilt inside a composable without creating an EntryPoint which will look like a boilerplate but we can do the following

1

2

3

4

@HiltViewModel

class NavigatorViewModel @Inject constructor(

private val navigator: Navigator

) : ViewModel(), Navigator by navigator

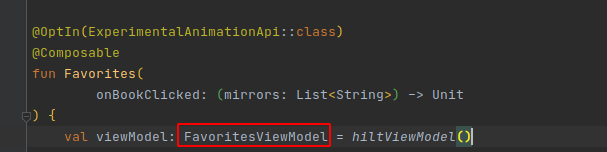

Navigator has the necessary elements for navigating and we can delegate them to this ViewModel which will be our navigator mechanism within the composable, we can end up having a logic where we only need navigation to destinations without any other logic and we can use the NavigatorViewModel

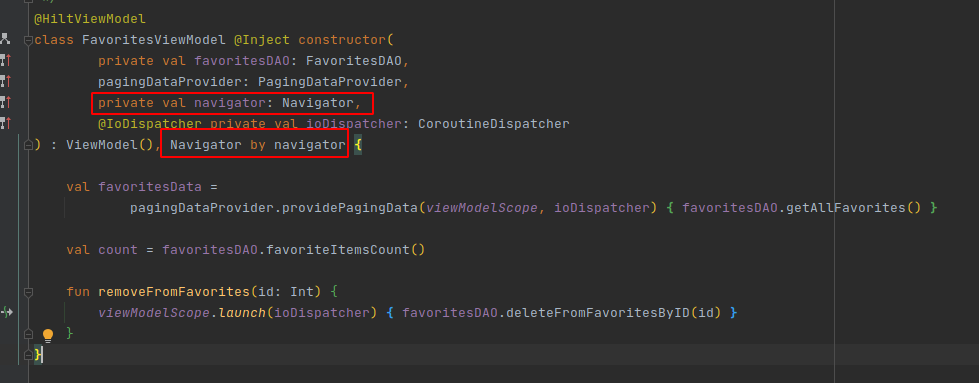

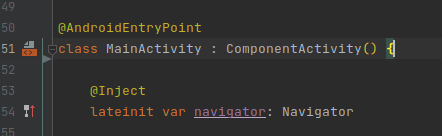

or we can have it injected into a view model (as the picture above) wherever we need the functionality for later on (pictures below)

The navigation destination is really simple, but yet confusing

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

object BookDetailsDestination : NavigationDestination {

override fun route(): String = BOOK_DETAILS_BOTTOM_NAV_ROUTE

override val arguments: List<NamedNavArgument>

get() = listOf(navArgument(BOOK_ID_PARAM) { type = NavType.IntType })

const val BOOK_ID_PARAM = "book"

private const val BOOK_DETAILS_ROUTE = "book_details"

private const val BOOK_DETAILS_BOTTOM_NAV_ROUTE = "$BOOK_DETAILS_ROUTE/{$BOOK_ID_PARAM}"

fun createBookDetailsRoute(bookID: Int) = "$BOOK_DETAILS_ROUTE/${bookID}"

}

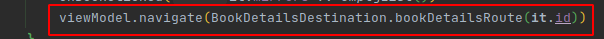

BookDetailsDestination holds our navigation route and arguments for the NavGraph, we add this so that the graph knows about this destination, this is separate from our createBookDetailsRoute that creates the route to navigate to the destination which we need to pass to our Navigator.navigate(route:String) in order to execute the navigation.

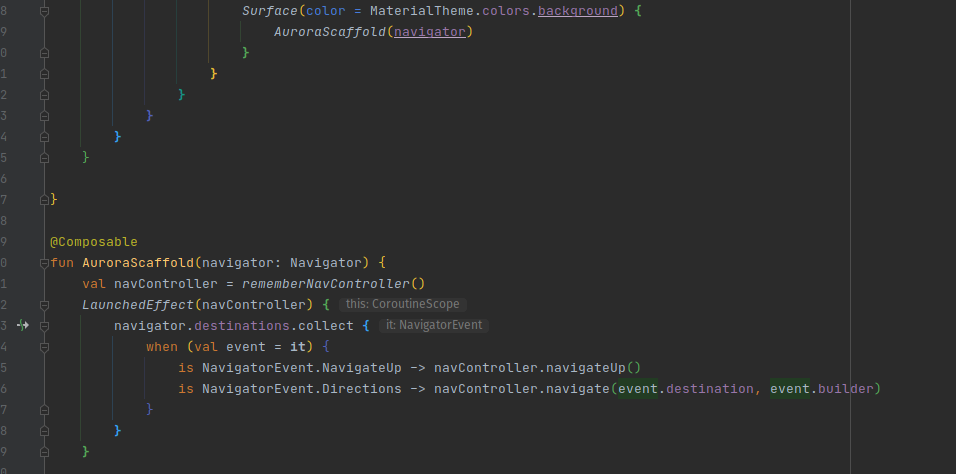

In order to wire the whole navigation we only need this included in the app level where we set up our navigation

Our navigation module end up looking really short

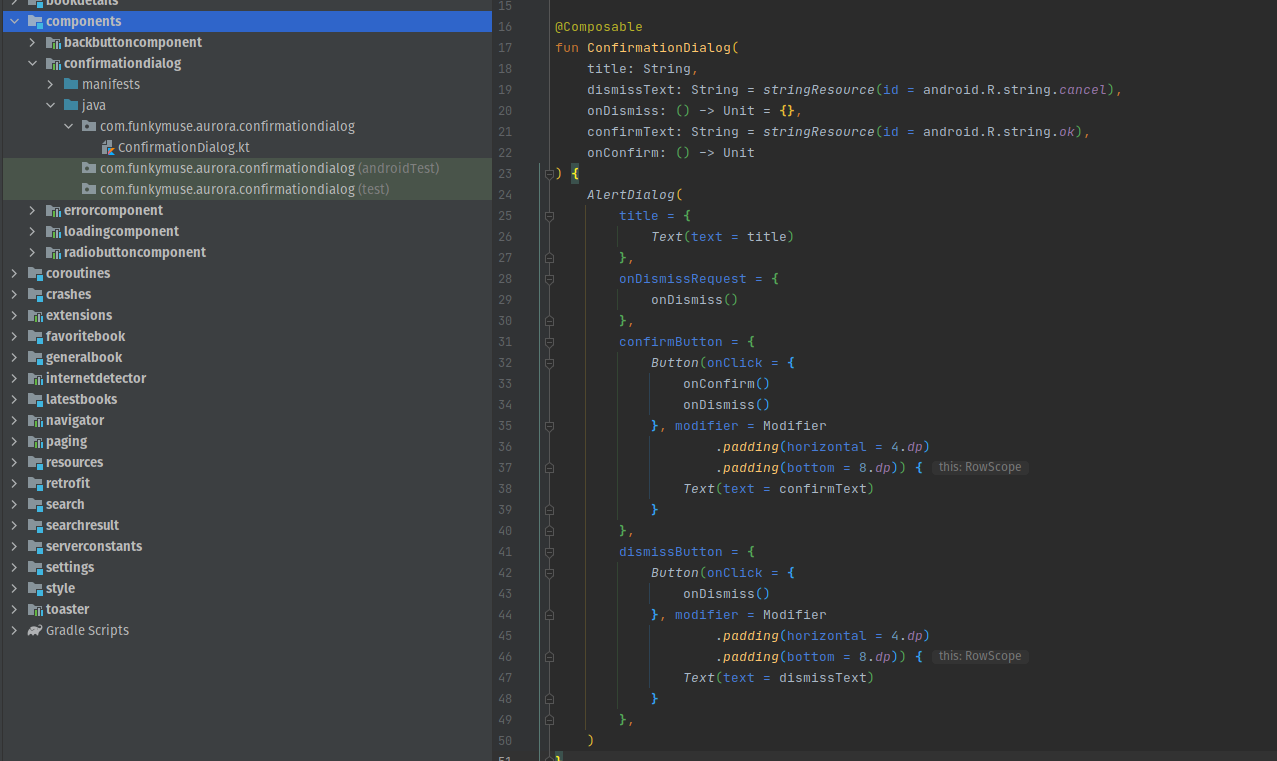

Structuring our application

Taking care of the navigation is the easy part, the next challenge is structuring the project.

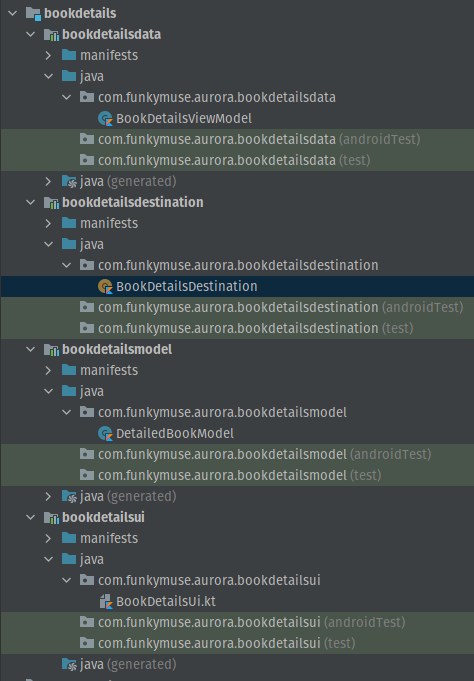

The approach I took for a client (due to NDAs i’m not supposed to reveal the app, it’s fitness related app), that now i’m using for a pet project, scaled pretty well, there were ~50 screens and everything was separated, every feature was a folder module, within that module there’s

- Data module -> Which loads the data and exposes it through a view model, can have the navigation as a delegate so that we don’t include the navigator with a separate

ViewModelor doesn’t have to if it doesn’t have to then your UI would need to include the navigator, whichever approach I took I ended up delegating the navigator to the data module inside the ViewModel - UI module -> Has only the UI part which uses the data module

- Destination module -> has the logic to navigate to the screen

- Model module -> has the necessary models that will be included in our Data module (#1)

Do note that the naming doesn’t really matter, some might use: business logic/layer etc etc.. that’s up for discussion internally in your team or however you feel like.

Your project will look like this or you might add another layer in between that creates a database

You might think, we’re creating a lot of modules, yes we are, we’re creating reusable parts that we can easily test and plug-in, plug-out or replace whenever we need to, some argue that good architecture is expensive, but have you tried bad architecture?

Compose UI enables us to hoist everything up to the top function and we can have everything as it’s own component, unreliant on anything else, uncoupled and does only it’s own thing.

For example a confirmation dialog

You can check out this approach in my pet project.

Also there’s another UI approach I took, not as mentioned in the project (as this project only has a small part of the UI modularized), which had the design, colors, styles, themes separated, as well as a building component for buttons, titles, subtitles etc.. but it’s not mentioned here as the UI parts for compose will change in the future and there will be better “best” practices, at the moment that’s how I saw it fit to modularize every single part of the UI as well, but this small pet project can’t really shine in that way, unless it grows in the future.

Thank you for reading and I hope you learnt something new.

Don’t forget to subscribe to the RSS feed in order to get updates for future posts.

Stay safe!