Hilt to the rescue, part 2

In the previous post Part #1, we’ve explored how to set up Hilt, the pre-defined components that come with it and migrated to Hilt from our Dagger sample.

In this blog post we’ll explore how to have our custom component live inside the Hilt hierarchy.

Custom components information

The documentation for custom components is bland, but does ask the most important question, Is a custom component needed?

In our case yes, but it does has some drawbacks

- Each component/scope adds cognitive overhead.

- They can complicate the graph with combinatorics (e.g. if the component is a child of the ViewComponent conceptually, two components likely need to be added for ViewComponent and ViewWithFragmentComponent).

- Components can have only one parent. The component hierarchy can’t form a diamond. Creating more components increases the likelihood of getting into a situation where a diamond dependency is needed. Unfortunately, there is no good solution to this diamond problem and it can be difficult to predict and avoid.

- Custom components work against standardization. The more custom components are used, the harder it is for shared libraries.

With those in mind, these are some criteria you should use for deciding if a custom component is needed:

- The component has a well-defined lifetime associated with it.

- The concept of the component is well-understood and widely applicable. Hilt components are global to the app so the concepts should be applicable everywhere. Being globally understood also combats some of the issues with cognitive overhead.

- Consider if a non-Hilt (regular Dagger) component is sufficient. For components with a limited purpose sometimes it is better to use a non-Hilt component. For example, consider a production component that represents a single background task. Hilt components excel in situations where code needs to be contributed from possibly disjoint/modular code. If your component isn’t really meant to be extensible, it may not be a good match for a Hilt custom component.

Custom components restrictions

- Components must be a direct or indirect child of the SingletonComponent.

- Components may not be inserted between any of the standard components. For example, a component cannot be added between the ActivityComponent and the FragmentComponent.

Creating a custom component

For this demonstration, we are having user management use case, for that sake let’s create a simple User class

1

data class User(val name: String, val surname: String, val id: Int)

and let’s define a contract upon which we’ll be building our user management

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

interface UserManagerContract {

val userID: Int?

val isUserLoggedIn: Boolean

fun logIn(loggedInUser: User)

fun logOut()

fun changeUser(user: User)

}

In order to have our custom component, let’s define our own custom scope

1

2

3

@Scope

@Retention

annotation class LoggedInUserScope

As with the Dagger series you’ve already know the building blocks of a component, which consists of

- The component itself

- Factory/builder

- Scope

Since Hilt already has a hierarchy we’ll need another building block (4th in our list) which is an Entry Point.

- Entry point

What is an Entry point?

An entry point tells which component/s should have an entry point, which essentially means that whenever the components are assembled by Hilt then and only then Hilt will know which components to include, as we’ve understood from the limitations of Hilt, every custom component we create is actually a sub-component of those pre-defined Hilt components, which then translates that every custom component that we create (sub-component) must have an Entry point accessor in order for us to get an instance of it.

DefineComponent

Every custom component must be annotated with @DefineComponent, this annotation has a parent parameter which you must include

our custom component will look like this

1

2

3

@DefineComponent(parent = SingletonComponent::class)

@LoggedInUserScope

interface LoggedInUserComponent

DefineComponent.Builder

The builder for a component must be annotated with, probably you know already

@DefineComponent.Builder

1

2

3

4

5

@DefineComponent.Builder

interface Builder {

fun provideUser(@BindsInstance user: User): Builder

fun build(): LoggedInUserComponent

}

As a standard Dagger2 builder, we’re binding an instance and returning the builder, then our build function has the duty to build the component.

I wish they had @DefineComponent.Factory so that we won’t need this fun build() function.

All in all, we’ll end up having our LoggedInUserComponent looking like

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

@DefineComponent(parent = SingletonComponent::class)

@LoggedInUserScope

interface LoggedInUserComponent {

@DefineComponent.Builder

interface Builder {

fun provideUser(@BindsInstance user: User): Builder

fun build(): LoggedInUserComponent

}

}

Entry point

Whenever we annotate our custom made entry point with @EntryPoint we must tell Hilt in which component we must have it installed, in our case we made our own LoggedInUserComponent

1

2

3

4

5

@EntryPoint

@InstallIn(LoggedInUserComponent::class)

interface LoggedInUserEntryPoint {

fun provideUserRepository(): UserRepository

}

inside we’re providing only one dependency (which we’ll create in a bit).

UserRepository

Our UserRepository will be implementing the contract we’ve created early UserManagerContract and we have to scope it to our custom scope @LoggedInUserScope.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

@LoggedInUserScope

class UserRepository @Inject constructor(private val userManager: UserManager) :

UserManagerContract {

override val userID: Int?

get() = userManager.user?.id

override val isUserLoggedIn: Boolean

get() = userID != null

override fun logIn(loggedInUser: User) {

userManager.logIn(loggedInUser)

}

override fun logOut() {

userManager.logOut()

}

override fun changeUser(user: User) {

userManager.changeUser(user)

}

}

The repository only delegates most of the duty to our UserManager.

UserManager

In our UserManager we need an instance of our LoggedInUserComponent and manage it’s lifecycle.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

@Singleton

class UserManager @Inject constructor(

private val loggedInUserProvider: Provider<LoggedInUserComponent.Builder>

) {

var user: User? = null

private set

var userComponent: LoggedInUserComponent? = null

private set

//we pretend that we're getting this User model from the backend

fun logIn(loggedInUser: User) {

// When the user logs in, we create a new instance of LoggedInUserComponent

userComponent = loggedInUserProvider.get().provideUser(loggedInUser).build()

user = loggedInUser

}

fun changeUser(user: User) {

logOut()

logIn(user)

}

fun logOut() {

userComponent = null

user = null

}

}

Since our UserManager will be available in our LoginFragment or LoginActivity we need it as a singleton, but the only thing that’s prone to change is our component and it’s lifecycle.

We’re using a provider since we only need to create the instance whenever there’s a logIn event.

Let’s go on and simulate our Log in scenario.

Log in scenario

For the brevity of this post, we keep the scenario inside one activity, but ideally you should do this from a LoginFragment or Activity

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

@AndroidEntryPoint

class MainActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

@Inject

lateinit var userManager: UserManager

private lateinit var userRepository: UserRepository

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

setContentView(R.layout.activity_main)

//we're simulating login, this would happen from LoginFragment or LoginActivity, for the sake of brevity we have it here

userManager.logIn(User(name = "test", surname = "test", id = 1))

//initializing the user repository wherever we need it after user is logged in

userRepository = EntryPoints.get(userManager.userComponent, LoggedInUserEntryPoint::class.java).provideUserRepository()

Log.d("USER ID", userRepository.userID.toString())

lifecycleScope.launch {

delay(1000)

userRepository.changeUser(User(name = "test", surname = "test", id = 2))

Log.d("USER ID", userRepository.userID.toString())

}

}

}

the most important piece of code here is

1

EntryPoints.get(userManager.userComponent, LoggedInUserEntryPoint::class.java)

What it does is, it generates our custom Entry point (LoggedInUserEntryPoint), every EntryPoint depends on the custom component that you create.

Once that piece of code executes you have an instance of LoggedInUserEntryPoint which holds the dependency you need, in our case UserRepository.

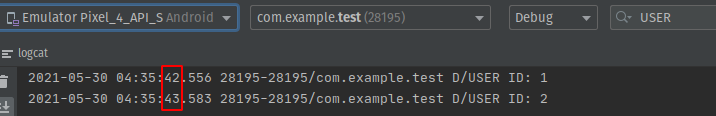

What we’re doing above is, we’re logging the user and after that 1 second delay we’re changing the user.

After we launch the application

It worked.

Scenario information

Do note that you’ll be needing events to handle log-in and log-out events, usually navigating user and restricting access, this is just a guide, not a full solution

Closing notes

This does seem a bit painful to manage a lot of these custom components, but if you split every management into a separate module, it’s managable.

Untill next part where we look at how to use Hilt in multi-module project + assisted inject.