Higher order functions, how, why and what not to do.

This is the last blog post of 2020, let’s end it with some Kotlin awesomeness.

Higher order functions are powerful and of course (the cliche) with great power comes great responsibility.

As the documentation says: A high-order function is a function that takes function/s as parameter/s or returns function/s.

How

We have our simple example:

1

2

3

fun highOrderFun(lambdaBlock: () -> Unit) {

}

highOrderFun is just a regular function, but as you can see… the parameter is of type () -> Unit, this means that the block of code that’s gonna enter as a parameter into the highOrderFun is gonna return Unit (a.k.a void for the Java wanderers).

1

2

3

4

fun highOrderFun(lambdaBlock: () -> Int) {

val calculationByTheOuterFunction: Int = lambdaBlock()

print(calculationByTheOuterFunction)

}

Now the lambdaBlock function parameter returns an Int, you can then decide what you wanna do with its result, in this case we print it.

1

lambdaBlock()

1

lambdaBlock.invoke()

These two ways call the function.

Higher order functions are also a good callback mechanism.

Let’s see an example

1

2

3

4

5

fun setTargetListener(callback: (Long, Int) -> Unit) {

val someCalculation = 50 + 27

val dateStamp = Date().time

callback(dateStamp, someCalculation)

}

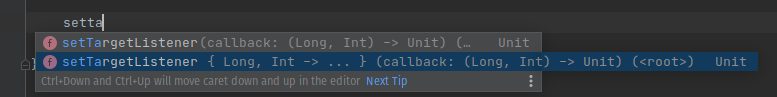

The function that enters setTargetListener as a parameter called callback, can provide two parameters on it’s own and returns Unit, so that we get something like this

1

2

3

4

setTargetListener { long, int ->

print("TIME MILLIS STAMP $long")

print("RESULT $int")

}

Kotlin has a beautiful syntax which provides you with this amazing functionality to remove the () after setTargetListener and just enjoy your lambda if it’s the last parameter.

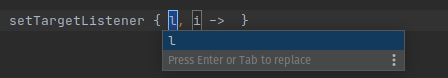

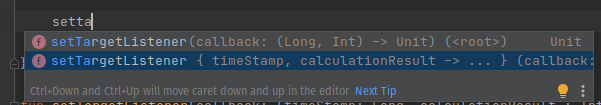

Now now, the setTargetListener is provided with a beautiful syntax by auto complete, but we see a major issue here, they’re called Long, Int, or once you choose the option they become

We don’t want that obscurity, let’s try something else.

1

2

3

4

5

fun setTargetListener(callback: (timeStamp: Long, calculationResult : Int) -> Unit) {

val someCalculation = 50 + 27

val dateStamp = Date().time

callback(dateStamp, someCalculation)

}

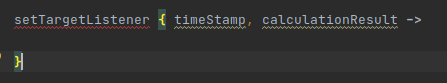

Now we’ve added names to our parameters inside the lambda block and now we get something that’s more readable.

1

2

3

setTargetListener { timeStamp, calculationResult ->

}

Now ain’t that sweet?

Let’s add a second lambda to our function

1

2

3

4

5

6

fun setTargetListener(firstLambda: () -> Unit, callback: (timeStamp: Long, calculationResult: Int) -> Unit) {

val someCalculation = 50 + 27

val dateStamp = Date().time

firstLambda()

callback(dateStamp, someCalculation)

}

and now an error arises

setTargetListener is expecting another lambda, what can we do?

In Kotlin there’s this sweet thing called default parameters, in case your firstLambda is something you rarely pass you can do this (this is just for demonstration purposes, real scenarios vary from use case to use case).

1

2

3

4

5

6

fun setTargetListener(firstLambda: () -> Unit = {}, callback: (timeStamp: Long, calculationResult: Int) -> Unit) {

val someCalculation = 50 + 27

val dateStamp = Date().time

firstLambda()

callback(dateStamp, someCalculation)

}

and the error is gone

One way is to pass an annonymous function

1

2

3

4

5

setTargetListener(fun (){

}){ timeStamp, calculationResult ->

}

and the other one is default values as aforementioned,

1

2

3

4

5

6

fun setTargetListener(firstLambda: () -> Unit = {}, callback: (timeStamp: Long, calculationResult: Int) -> Unit = { _, _ -> }) {

val someCalculation = 50 + 27

val dateStamp = Date().time

firstLambda()

callback(dateStamp, someCalculation)

}

where the default values are as

1

{ _, _ -> }

which means two parameters and names omitted with underscores just as you would, when you wouldn’t be using the lambda and the compiler will warn you to underscore them for brevity.

We’re advancing towards new horizons.

1

2

val subtraction = { x: Int, y: Int -> x - y }

operation(10, 5, subtraction)

1

2

3

fun operation(x: Int, y: Int, mathOperation: (Int, Int) -> Int) {

print(mathOperation(x, y))

}

In Kotlin, functions are first-class, which also means they can be variables, stored in data structures and as we have seen above, parameters to other functions.

Our value subtraction is nothing complicated than writing

1

fun subtraction(x: Int, y: Int) = x - y

the function operation is already clear as we’re knowledgable so far, but this case has given us the chance to explore something even cooler.

if we have our function

1

fun subtraction(x: Int, y: Int) = x - y

then we can do

1

operation(10, 5, ::subtraction)

the :: operator is a call by function reference, it knows how many arguments the function has and it’s providing them as in order as they are in the operation function, meaning x = 10 and y = 5 and returning the result of their subtraction as an Int.

I’d suggest you take a break here.

After you’re back, you can freely feel like singing “I’m back” by Eminem.

We’re going depper now, exploring the receiver type.

1

2

3

4

5

6

fun setTargetListener(actionOnTime: Long.() -> Unit): Int {

val someCalculation = 50 + 27

val dateStamp = Date().time

dateStamp.actionOnTime()

return someCalculation

}

Our lambda now expects some object, but the syntax is weird at first?

1

Long.() -> Unit

I assure you, it’s easy.

Our Long. that dot after our Long means we have to call a function to an object of a long type, but which function, oh yes, the one that goes after the dot () -> Unit

in our case, which means inside the setTargetListener we have to find some object of a type Long and call the same function as a paramater on that object, in our case dateStamp.

We’re in this situation when the object cannot be named as we want and had seen in the previous example where we could’ve given custom names, now it’s called this, since it’s THIS instance you’re poking with your lambda function.

What if I told you, you already know the next thing you see?

You may know it by other name also without the defaultNonNullValue, the famous scope function let.

Shortly i’ll explain scope functions, the more I explain, the more I’ll confuse you, so… i’ll keep it simple.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

fun <RECEIVER_TYPE, RETURN_TYPE> RECEIVER_TYPE?.nullCheckOrDefault(defaultNonNullValue: RETURN_TYPE, block: (RECEIVER_TYPE) -> RETURN_TYPE): RETURN_TYPE {

return if (this != null) {

block(this)

} else {

defaultNonNullValue

}

}

1

2

3

4

5

val stringLength: Int = someNullString.nullCheckOrDefault(5) {

it.length

}

print(stringLength)

Another thing we learned along the way is that generics in Kotlin are also sweet.

Okay let’s take it step by step:

- RECEIVER_TYPE is the first generic and telling us what type we’re gonna call the function onto, in our case someNullString is a String

- RETURN_TYPE tells us what our function would be returning, in our case if the someNullString is null we’ll have a defaultNonNullValue which is the same type as the RETURN_TYPE in our case Int, otherwise if the someNullString is not null we’ll return its length.

- block(RECEIVER_TYPE) -> RETURN_TYPE, means that the lambda will have an argument the same as the type we’re calling the function onto (poking it which is RECEIVER_TYPE? the question mark is because we want to call it on nullable object) and the RETURN_TYPE is already specified once you say what the defaultNonNullValue would be in this case Integer or the return value inside the block where it.length is.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

inline fun <RECEIVER_TYPE, RETURN_TYPE> RECEIVER_TYPE?.nullCheckOrDefault(defaultNonNullValue: RETURN_TYPE, block: (RECEIVER_TYPE) -> RETURN_TYPE): RETURN_TYPE {

return if (this != null) {

block(this)

} else {

defaultNonNullValue

}

}

If you notice something, now we have another citizen, inline.

What inline does is, when Kotlin gets compiled to Java byte code, the whole function body of our parameter lambda named block would be pasted wherever it’s called instead of a generic Function object which would add boxing overhead when primitive types are being used and an object is created of course.

There’s more to say about inline, crossinline, noinline, but that’s gonna be another blog post.

Why

If you’re using Kotlin it’s not a question of why.

Instead of using callable objects every time as in avoiding a whole mess of abstracts/interfaces.

Also functional programming wouldn’t be possible without lambdas.

This felt quick didn’t it?

It’s a simple answer.

And now we’re closing in at the scariest part, what not to do.

Let’s say we have this class

1

2

3

4

5

inline fun processSuperPower(powerBlock: () -> Int): Int {

val powerBlockBeforeProcess = powerBlock()

powerBlockBeforeProcess.compareTo(Int.MAX_VALUE)

return calculateMassOfTheSunAndGetHowManyChocolatesAreOnMars(powerBlockBeforeProcess)

}

Okay, we’re good citizens and we’ve inlined it, i.e saving the compiler some overhead and then someone uses it like the nightmare you’re about to see

at first you may think, but there’s no problem at all, let’s explain why there’s a big problem.

There’s value initialization, branching and those two branch clauses that call additionally two functions once inside the branch, we don’t know how they’re implemented (we’re hoping they’re short and respecting clean code principles).

What we shouldn’t do?

Do not use big functions as arguments, since most modern CPUs take those inline functions as shortcuts but you’re adding pressure to the instructions cache, the bigger the function, the bigger the pressure you add, which may result running slower than a normal non-inlined function (people may argue that modern hardware barely notices this, it’s true, but few milliseconds there and few milliseconds there end up making second/s and somehow your system is slowed but you’ve no idea).

inline when all functional type parameters are called directly or passed to other inline function

You should consider inlining if at least one of your functional type parameters can be inlined, use noinline for the others (again respect #1).

Another use case is reified type parameters, which require you to use inline (we’ll talk about that in another blog post).

Escape inilining functions when you’re declaring an anonymous function directly into the parameter lambda, a new function is created every time the code that uses when it runs, which in some cases makes little to no difference at all, but in other cases it may be something to consider for performance reasons (if doing things in a loop).

You can check out my repo that’s open sourced and learn a trick or two from some of the helpers/extension functions i’ve made for Android development.

If you wanna read an overused joke, cya in 2021.

Thank you for your patience and wholehearted attention.